Self-care practices intervention among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Ibadan, Nigeria: a quasi-experimental study

Abdullahi Ademola Akinniran, Sufiyan Abu Muyibi, Olushola Aisha Mosuro, Adedotun Adeyinka Adetunji, Waheed Adeola Adedeji

Corresponding author: Waheed Adeola Adedeji, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

Received: 19 Apr 2022 - Accepted: 13 Mar 2023 - Published: 27 Mar 2023

Domain: Family Medicine,Internal medicine,Health education

Keywords: H-SCALE, adherence, self-care, hypertension, blood pressure, community-based setting, Specific Adapted Instruction Protocol

©Abdullahi Ademola Akinniran et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Abdullahi Ademola Akinniran et al. Self-care practices intervention among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Ibadan, Nigeria: a quasi-experimental study. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2023;11:53. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2023.11.53.35002]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/11/53/full

Research

Self-care practices intervention among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Ibadan, Nigeria: a quasi-experimental study

Self-care practices intervention among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Ibadan, Nigeria: a quasi-experimental study

Abdullahi Ademola Akinniran1,2, Sufiyan Abu Muyibi1, Olushola Aisha Mosuro1, Adedotun Adeyinka Adetunji1, ![]() Waheed Adeola Adedeji3,4,&

Waheed Adeola Adedeji3,4,&

&Corresponding author

Introduction: World Health Organization recommends self-care education to prevent and treat hypertension. This study determines the effect of 3-month self-care practices on Blood Pressure (BP) control among adults with uncontrolled hypertension.

Methods: this single-centred quasi-experimental parallel study design was conducted in a Community Medical Centre in Ibadan. The study recruited adults aged 40 years and above with uncontrolled hypertension. Of the 502 patients screened, 274 were randomised to intervention (137 participants). The intervention group received a Specific Adapted Instruction Protocol on self-care practices in hypertension, while the control group received non-specific clinical instruction. Awareness and performance of hypertension self-care practices were obtained at baseline and three months after the intervention. The primary endpoint was BP control, while the secondary outcomes were changes in participants' awareness and performance of hypertension self-care practices.

Results: of the 274 participants randomised, the mean age, intervention versus control group, was 63.2 ± 11.9 versus 61.4 ± 12.4 years. At three months post-intervention, 122(89.1%) versus 85(62.0%) participants had BP controlled. Participants in the control group had an increased risk of poor BP control after intervention: relative risk (95% CI, p-value), 2.62 (1.62-4.81, p<0.0001). There was a 23.3% and 25.3% increase in the awareness level of hypertension self-care practices in the intervention and control groups. There was no difference in the effect of an intervention on the awareness of hypertension self-care practices between the intervention and control group, relative risk (95% CI, p-value), 0.67(0.36-1.58, p=0.124).

Conclusion: a 3-month self-care practice intervention improved BP control and awareness of hypertension self-care practices among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Ibadan.

Uncontrolled hypertension accounts for a substantial proportion of cardiovascular deaths and morbidity resulting from stroke, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and kidney failure. Globally, hypertension is poorly controlled [1-4]. In the US, treated, but uncontrolled adults with hypertension had a higher risk of all causes, heart disease-specific and cerebrovascular disease-specific mortality [5]. Among individuals with hypertension, an estimated 35.8 million (53.5%) did not control their hypertension [6]. In India, only one-third of patients with hypertension were on antihypertensives, and only 10 to 20% had optimal blood pressure control [3]. In Africa, in addition to the lower awareness of hypertension, there was generally poor blood pressure control across the region [4]. Similarly, blood pressure control among adults with hypertension remains very poor in Nigeria. For example, Adeoye et al. found only 25.4% of subjects studied in a clinical setting had blood pressure well controlled [7].

Management of hypertension consists of preventive behaviour, adherence to treatment and risk-factor management [8]. Self-care practices have been shown to assist in the attainment of better blood pressure control among hypertensive patients [9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends self-care education to prevent and treat chronic diseases, including hypertension, because it encourages involvement in their care and improves adherence to the treatment regimen, minimising complications and disability associated with chronic problems [10]. Patient self-care behaviours crucial to controlling BP encompass medication adherence and lifestyle factors such as non-smoking tobacco, weight management, low salt intake and low-fat diet, adequate physical activity, moderation in alcohol consumption, BP self-monitoring, regular doctor visits and stress reduction [8,11]. Randomised Control Clinical Trials have demonstrated the positive effects of self-care activities, including Self-measured blood pressure (SMBP) monitoring on BP control [12]. In a systematic review, SMBP with or without additional support was reported to lower BP than usual care before 12 months [13].

Previous studies identified knowledge of self-care management, age, gender, income, and education level have a positive relationship with self-care management of hypertension [14,15]. Studies examining factors affecting the management of hypertension have less frequently addressed self-care practices. Also, there is a challenge in formulating new research on self-care practices, since poor adherence to self-care practices may be related to poor blood pressure control rates [16]. In addition, there is lack of studies on self-care practices among patients with uncontrolled hypertension in Nigeria. This study determined the effect of a 3-month self-care intervention practices on blood pressure control among adults with uncontrolled hypertension attending a Community Medical Center in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Study design and setting: the study employed a single-centre, quasi-experimental, single-blind, parallel-group design. The study was conducted at Agbeke Mercy Medical Center (AMMC), Oluyole Cheshire Home, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. It is an affiliate of the Family Medicine Department, University College Hospital, Ibadan. The outpatient unit attends to about 400 patients monthly, with 260(65%) having hypertension. Despite ongoing treatment, one hundred and fifty-six (60%) patients with hypertension had BP >140/90mmHg. Of all patients with uncontrolled BP attending the clinic, 62 (40%) were new to AAMC, while 94 (60%) received follow-up care. Family Physicians and resident doctors from the University College Hospital, Ibadan man AMMC.

Study population: consenting adult patients aged 40 years and above with uncontrolled hypertension receiving treatment for at least six months at AMMC within stipulated periods (September 2017 to March 2018). Exclusion criteria included patients who presented with a medical emergency, hypertensive heart disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, couples, and psychologically unstable patients.

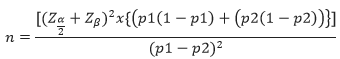

Sample size and sampling: the sample size was calculated using the formula for the comparison of two groups.

In a study in Benin City, Nigeria, the proportion of hypertensive adults with good self-care practices was 16.5% [9]. Assuming p1-p2=0.15(15%), Z α/2(5% level of significance) =1.96, Zβ (80% power)=0.84, and after adjusting for the 10% non-response, a sample of 137 participants was obtained in each group. A sampling interval of two (2) was determined by dividing the sampling frame of 468 adults with uncontrolled hypertension in three (3) months by the sampling size of 274. Case notes were reviewed, and eligible participants were identified. The first patient was selected randomly by balloting Yes or No. Every second patient was approached for consent until the sample size was attained.

Randomisation and masking: the participants were randomly allocated into two groups (Intervention and control). A minimum of five (5) eligible participants were recruited per day until the estimated sample size of 274 was attained. This process was followed by a 3-month intervention period (intervention group) and routinely followed-up clinic visits in the control group. Only the participants were masked.

Interventions: participants in the intervention group were trained on proper blood pressure (BP) measurement using automated BP apparatus (Omron HEM-5001 device) and given the following Specific Adapted Instruction Protocol on self-care practices in hypertension [18]: 1) Check your BP at your home, nearby clinic or at a pharmacist outlet on at least two days a week (say Tuesday and Friday), in the morning between 6:00 AM and 9:00 PM and the night between 6:00 PM and 9:00 PM. Come along with the record of measurements at each clinic visit. 2) Do a specific exercise activity (such as swimming, brisk walking, or biking) other than what you do around the house or as part of your work for 30 minutes four to five times per week. 3) Reduce adding salt to food when cooking, and do not add salt to your food at the table. 4) Eat five or more servings of fruit and vegetables daily, e.g., five medium-sized oranges, five apples, vegetables (hundred naira worth), pawpaw, five medium-sized bananas, watermelon, and carrots (hundred naira worth). 5) Use boiling or steaming instead of frying when cooking. 6) Avoid eating fatty foods such as 'egusi' (melon seed), 'ogbono', mayonnaise etc. 7) Practice moderation in drinking alcohol daily (one bottle; 600ml of larger beer or less for men, half bottle; 300ml of larger beer or less for women). 8) Avoid staying in a room or riding in an enclosed vehicle while someone is smoking or avoid smoking cigarettes. 9) Cut out drinking sugary drinks, like coke, big cola, La Casera, and sweet tea. 10) Substitute routine foods for healthier foods such as cabbage, garden egg, walnut cucumber, and vegetable. 11) Take your BP medication as recommended and come along with your left-over BP medication. 12) Try to stay away from anything and anybody that causes stress. 13) Avoid beverages such as bournvita, milo, ovaltine and pronto. 14) Use decaffeinated drinks such as 'Tetley decaf'. 15) Use one-third of evaporated tin milk or one sachet (3´ crown and olympic) or two powdered skimmed milk dessert spoons (Marvel skimmed or Dano slim) daily. 16) If overweight or obese, limit calorie intake to 1500kcal (two thin slices of yam or one wrap of 'Eko' or three thin slices of bread or 10-12 dessert spoons of rice/beans or 5-6 dessert spoons of 'amala'/semovita/pounded yam/´tuwo´/´eba´) 17) Meal timing; breakfast:7-8:00 AM, lunch: 12-1:00 PM, dinner: 6-7:00 PM. 18) You will be followed up every two weeks over the eight weeks, then at 12 weeks. 19) Pre- and post-intervention data will be collected from you. Participants in the intervention group attended an information reinforcement and clinic session every other week for eight weeks.

The participants in the control group were given routine, non-specific clinic instructions, which include the following: 1) You can monitor your blood pressure (BP) at your home, at a nearby clinic or at a pharmacist outlet. 2) If overweight or obese, limit calorie intake. 3) Do not smoke cigarettes. 4) Eat more fruit and vegetables daily. 5) Do regular exercise for 30 minutes four to five times per week. 6) Practice moderation in drinking alcohol. 7) Take your BP medication as recommended. 8) Reduce salt intake. The study protocol required six visits. On the first visit, participants from the intervention group were introduced to the study, signed an informed consent form, completed a questionnaire, and received Specific Adapted Instruction Protocol on self-care practices. Routine, non-specific clinic instructions were given to the control group. The second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth visits occurred in the second, fourth, sixth, eighth and twelve weeks, respectively. The researchers and trained research assistants did BP and anthropometric measurements at every visit. Also, the awareness of self-care practices questionnaire and adapted Hypertensive Self-Care Activities Level Effects (H- SCALE) (interviewer-administered) tool were completed at baseline and 12 weeks. The H-SCALE tool [18] is recommended by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7). H-SCALE has been validated in many countries, including Nigeria [9,19,20]. It encompasses six hypertension self-care behaviours, including medication adherence, non-smoking tobacco, weight management, low salt and low-fat diet, physical activity and moderation in alcohol consumption. Items in each of the six hypertension self-care domains were assessed and scored according to the methods described by Warren-Findlow et al. [18]. The Level of Awareness of self-care in hypertension questionnaire was adapted from the six domains of Hypertension self-care behaviours recommended by the JNC 7 [21] and modified for the suitability of the environment. The individual answer 'Yes', 'No', or 'Don't know' to these six declarative statements. Each "yes" answers score +1, and" no" or" I don't know" score 0. The summated scores ranged from 0 to 6. Participants with scores equal to or greater than 4 points suggested good awareness, while scores equal or less than 3 points suggested poor awareness. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were acceptable (α= 0.78).

Outcomes: the primary endpoint was BP control, measured as the proportion of patients achieving BP of less than 140/90 mmHg from baseline to three months after the commencement of the intervention. The secondary outcomes were changes in BP measurement(mean), awareness of self-care practices in hypertension using the awareness scale, and performance of hypertension self-care practices using H-SCALE from baseline to three months after the intervention.

Statistical analysis: data were entered, cleaned, and analysed using SPSS version 23. Categorical variables were summarised using frequency and percentages, while mean (standard deviations) were computed for quantitative variables when normally distributed; otherwise, with median (interquartile range). The categorical variables were compared between the control and intervention groups using Chi-square. The awareness of self-care practice was scored and ranked (good and poor) and was compared using the chi-square test for the intervention and control at the baseline and end of the three-month intervention. The practice of self-care in hypertension (all ranked into adhere/non-adhere) and BP control (yes/no) measured from baseline to the end of three months were compared using the chi-square test. The mean difference in SBP and DBP between baseline and three months was compared for control and intervention groups using an independent T-test. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%.

Ethical consideration: the study was approved by the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital ethical review committee (UI/EC/17/0001). Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Study Participants: five hundred and two participants were screened. And 274 consenting adults underwent randomisation: 137 participants were randomised to each group (Figure 1). The study was conducted between October 2017 and March 2018. Analyses were carried out on all the participants. The mean age in the intervention and control groups was 63.18 (±11.88) and 61.35 (±12.43) years, respectively. Most of the participants were married, 87(63.5%) versus 80 (58.4%) and Yoruba by tribe, 128 (93.4%) versus 124(90.5%). The mean duration of hypertension was 4.95 (±4.19) versus 4.10 (±3.04) years. Ninety-two (67.1%) versus 79(57.7%) had overweight, or obesity, and 64(46.7%) versus 68(49.6) had at least grade 2 hypertension. Most participants had a good awareness of hypertension self-care, 103(75.2%) versus 94(69.2%). The characteristics of the participants in the intervention and control groups were broadly similar at baseline, p >0.05 (Table 1).

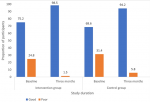

Awareness of Hypertension Self-Care Practices among the Study:

Participants: the two groups were similar at baseline on the level of awareness of hypertension self-care practices (Figure 2), and there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups (p=0.226). There was an increase in the hypertension self-care practices awareness among participants in the intervention group from baseline till after three months and was statistically significant (p= 0.013). Similarly, there was a 25.6% increase in the level of awareness of hypertension self-care practices among participants in the control group after three months, which was statistically significant (p= 0.006) (Table 2). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the effect of the 3-month intervention on the awareness of hypertension self-care practices between the intervention and control group, relative risk (95% Confidence interval, p-value), 0.67(0.36-1.58, p=0.124).

Assessment of Performance of Hypertension Self-Care Practices among the Study Participants Using Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effect (H-SCALE) Tool: in the intervention group, there was a statistically significant increase in the H-SCALE of participants from baseline to three months after the commencement of the intervention (p<0.05). Also, in the control group, participants had a statistically significant increase in the H-SCALE from baseline to three months after the commencement of medication adherence, non-smoking and alcohol abstinence(p<0.05). However, there was no statistically significant improvement in the control group's adherence to low fat, low salt diet and weight management (Table 3).

Blood pressure (mmHg) control among the study participants: at the end of three months, most of the participants, 122(89.1%) vs 85(62.0%) in the intervention group vs the control, had their BP controlled. Participants in the control group had an increased risk of poor BP control after three months: relative risk (95% Confidence Interval, p-value), 2.62 (1.62-4.81, p<0.0001). Also, there was a statistically significant reduction in the participants' mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline until three months (Table 4). There was a statistically significant mean difference in the SBP (p=0.0016) and DBP (p=0.0143) of the participants in the intervention and control groups (Table 5). Figure 3 shows a consistent reduction in the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the study participants, though with a greater mean decrease in the blood pressure in the intervention group.

Self-care practices in managing hypertension have been shown to improve blood pressure control, but there is a lack of studies documenting the effect of self-care practices interventions on BP control in Nigeria. In this study, among adults with uncontrolled hypertension attending community health care, a 3-month self-care practice using Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effect (H-SCALE) intervention statistically significantly increased the awareness of hypertension self-care practices, and an improvement in the blood pressure control of the participants. There was a significant increase in the intervention group's awareness of hypertension self-care scores. Studies have generally documented the positive effect of educational intervention on behavioural and lifestyle changes. Similar findings among the control group may be related to the exchange of information among the participants, since they were from the same community. The findings are comparable to the work of Ramaiah et al. in Dharmapuri, India. They reported an improvement in knowledge of hypertension scores among the participants after the intervention [22]. Similarly, Al-Wehedy et al. in Egypt, documented a significant improvement in hypertension knowledge among the participants after the intervention; however, the study lasted for six months [23]. Also, comparable to this study, a study in the West of Ireland reported a positive effect after 4-month of intervention [24].

After the intervention, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of participants adhering to medication, low salt diet, non-smoking cigarettes, alcohol abstinence, physical activity, and weight management. Contrarily, a slight increase in the proportion of participants who adhered to medication, low salt diet, physical exercise and weight management in the control group were not statistically significant. The findings in the control group may be justified by obtaining information about the self-care practice from their healthcare providers or the participants in the intervention group. Similarly, in Egypt, Al-Wehedy et al. reported a significant improvement in the study group's total and all dimensions of lifestyle patterns compared with the control [23]. The magnitude of the BP control and the reduction in the post-intervention mean SBP and DBP levels of the participants in the intervention group was substantial and comparable to similar previous studies in Turkey [25] and Egypt [23,26]. Also, Daniali et al. in a randomised control trial among Iranian on the impact of educational intervention on self-care behaviours among overweight hypertensive women reported a significant reduction in systolic and diastolic BP in the intervention group after six months of intervention [27]. Uhlig et al. also documented that self-measured BP monitoring lowers BP compared with usual care [13]. In addition, the findings were similar to a systematic review by Glynn et al. on interventions used to improve the BP control of patients with hypertension. Most RCTs were associated with improved blood pressure control and reduced mean SBP and DBP [12]. Crouch et al. in a systematic review, also reported a drop in study participants' blood pressure at six months post-intervention [28].

The mean differences within-group comparisons of SBP and DBP were more prominent in the intervention group than in the control group. Similarly, Vallès-Fernández et al. in Spain, among patients with hypertension, documented significant mean differences within-group comparisons of SBP and DBP, larger in the intervention group than in the standard care group. The more significant mean difference was detected in SBP and DBP at 1-year follow-up [29]. This differed from this study, in which the intervention lasted only three months. In this study, 10.9% versus 38.0% in the intervention and the control group had uncontrolled BP despite the treatment and intervention. Arguably, there is a possibility that participants might fail to adopt hypertension self-care practices and the standard lifestyle modifications in the intervention and control groups, respectively. Also, beyond the scope of this study, other factors may be responsible for poor BP control among the participants. For example, the effect of drug-drug interactions, like NSAIDs and some antihypertensives, among participants with osteoarthritis. Similarly, Glynn et al. in a systematic review, reported that BP goals were achieved in only 25-40% of the patients who took antihypertensive drug treatment [30]. Also, Ojo et al. on the appraisal of BP control and its predictors among patients with hypertension seen in a primary health care clinic of a tertiary hospital in Western Nigeria, reported only 46.4% of their participants had BP controlled [31]. Although the self-care practices affected BP control, the study showed that most participants did not adhere to most of the domains of the H-SCALE. One of the possible explanations may be the short duration of the intervention. However, there was no statistically significant effect of self-care practices (six domains) on BP control in both groups. The findings are comparable to previous studies. However, these studies lasted for a longer duration [12,23,30,32-34].

Literature supported the higher efficacy of self-care practices counselling over routine clinical information regarding achieving more BP control, as reported in this study [9,14,18,25,35-37]. However, the differences mentioned above in BP control of participants from baseline to the end of three months were slight in effect sizes compared too few other interventional studies. This finding might be due to the short-term assessment duration of this study's intervention program compared to a longer period of evaluation of the self-care intervention program in the other comparable studies. The limitations of this study include the short-term assessment of self-care interventions, which may not be enough to achieve the desired large effect on self-care practices and BP control. The H-SCALE tools used are highly susceptible to recall bias. Also, participants with other comorbidities like osteoarthritis were not excluded and might have influenced the research findings, including physical activity. The change or improvement in the performance of self-care practice among participants might be because of this study, but not necessarily because of the Intervention (Hawthorne effect). However, this study has many strengths, including achieving a BP control among 75.5% of the participants. It increased the awareness of self-care practices of most of the participants. This study also contributed to the knowledge of self-care interventions to improve BP control among people in low-middle-income countries (LMICs).

The provision of Specific Adapted Instruction Protocol on Self-Care Practices for three months positively improved the performance of hypertension self-care practices. It significantly enhanced the BP control of adults with uncontrolled hypertension within a community-based setting. Further studies of longer duration are suggested in Nigeria to assess the long-term benefits of using H-SCALE tools.

What is known about this topic

- Uncontrolled hypertension accounts for a substantial proportion of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality;

- World Health Organization recommends self-care education to prevent and treat chronic diseases, including hypertension;

- Despite the importance, available studies and evidence on self-care practices for hypertension are from developed countries.

What this study adds

- A short-term self-care practice intervention improved blood pressure control and awareness of hypertension self-care practices among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Nigeria;

- The intervention may provide the means to improve BP control and the level of awareness of hypertension self-care practices among adults with uncontrolled hypertension2.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abdullahi Ademola Akinniran was involved in the study design conceptualization, data collection, analysis and interpretation and manuscript drafting. Waheed Adeola Adedeji was involved in the study design conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and review. Sufiyan Abu Muyibi, Olushola Aisha Mosuro, and Adedotun Adeyinka Adetunji provided advice on study design, interpretation of the data, and manuscript review. All the authors read and agreed to the final manuscript.

The authors would like to thank all the study participants and members of staff of Agbeke Medical Centre (AMMC), Oluyole Cheshire Home, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. The authors equally acknowledge the support received from the management of the University College Hospital, Ibadan, and Federal Medical Centre, Uguru, Yobe State, Nigeria.

Table 1: baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants (N=274)

Table 2: awareness of self-care practices of the participants in the Intervention and control group at the baseline and the end of three months

Table 3: Hypertension Self-Care Practices Using Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effect (H-SCALE) tool among study participants at baseline and three months

Table 4: blood pressure control among the study participants at baseline and end of three months

Table 5: effect of intervention on the mean difference in the BP control among participants in the intervention and control group after three months

Figure 1: flow diagram of study recruitment and follow-up

Figure 2: awareness of Hypertension Self-Care Practices of Participants at Baseline and the end of three months in the intervention and control group

Figure 3: trend lines showing changes in mean SBP and DBP of the participants from week 0 to 12 weeks in the intervention and control group

- Raji YR, Abiona T, Gureje O. Awareness of hypertension and its impact on blood pressure control among elderly Nigerians: report from the Ibadan study of aging. Pan Afr Med J. 2017 Jul 13;27:190. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Valderrama AL, Gillespie C, King SC, George MG, Hong Y, Gregg E. Vital Signs: Awareness and Treatment of Uncontrolled Hypertension Among Adults- United States, 2003-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(35). Google Scholar

- Anchala R, Kannuri NK, Pant H, Khan H, Franco OH, Di Angelantonio E et al. Hypertension in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension. Journal of hypertension. 2014;32(6):1170. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kayima J, Wanyenze RK, Katamba A, Leontsini E, Nuwaha F. Hypertension awareness, treatment and control in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013 Aug 2;13:54. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Zhou D, Xi B, Zhao M, Wang L, Veeranki SP. Uncontrolled hypertension increases risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in US adults: the NHANES III Linked Mortality Study. Sci Rep. 2018 Jun 20;8(1):9418. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Yoon SS, Gu Q, Nwankwo T, Wright JD, Hong Y, Burt V. Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United States, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension. 2015;65(1):54-61. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Adeoye AM, Adebiyi A, Tayo BO, Salako BL, Ogunniyi A, Cooper RS. Hypertension Subtypes among Hypertensive Patients in Ibadan. International Journal of Hypertension. 2014;2014:295916. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, Dickson VV, Dunbar SB, Lee CS et al. Self-care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6(9):e006997. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Egbi O, Ofili A, Oviasu E. Hypertension and diabetes self-care activities: A hospital based pilot survey in Benin City, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2015 Jun;22(2):117-22. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Narasimhan M, Allotey P, Hardon A. Self care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: a conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. BMJ. 2019 Apr 1;365:l688. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Han H-R, Lee H, Commodore-Mensah Y, Kim M. Development and validation of the hypertension self-care profile: a practical tool to measure hypertension self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014 May-Jun;29(3):E11-20. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 Mar 17(3):CD005182. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Uhlig K, Patel K, Ip S, Kitsios GD, Balk EM. Self-measured blood pressure monitoring in the management of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;159(3):185-94. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Warren-Findlow J, Seymour RB. Prevalence rates of hypertension self-care activities among African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(6):503-12. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Akpa MR, Alasia DD, Emem-Chioma PC. An Appraisal of Hospital Based Blood Pressure Control in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Nigerian Health Journal. 2008;8(1-2):27-30. Google Scholar

- Mendes CR, Souza TL, Felipe GF, Lima FE, Miranda MD. Self-care comparison of hypertensive patients in primary and secondary health care services. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2015 Nov;28:580-6. Google Scholar

- Sakpal TV. Sample size estimation in clinical trial. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2010 Apr;1(2):67-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Warren-Findlow J, Basalik DW, Dulin M, Tapp H, Kuhn L. Preliminary validation of the Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effects (H-SCALE) and clinical blood pressure among patients with hypertension. Journal of clinical Hypertension (Greenwich, Conn). 2013 Sep;15(9):637-43. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Niriayo YL, Ibrahim S, Kassa TD, Asgedom SW, Atey TM, Gidey K et al. Practice and predictors of self-care behaviors among ambulatory patients with hypertension in Ethiopia. PloS one. 2019;14(6):e0218947. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Krinner LM, Warren-Findlow J, Thomas EV, Coffman MJ, Howden R. Validation of Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effects (H-SCALE). InAPHA's 2018 Annual Meeting & Expo (Nov. 10-Nov. 14) 2018 Nov 11. APHA. Google Scholar

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560-72. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ramaiah P. A study to assess the effectiveness of structured teaching program on the knowledge of lifestyle modification of hypertension among the patients with hypertension in a selected private hospital at Dharmapuri district. Int J Educ Sci Res (IJESR). 2015;5(1):35-8. Google Scholar

- Al-Wehedy A, Abd Elhameed SH, Abd El-Hameed D. Effect of lifestyle intervention program on controlling hypertension among older adults. Journal of Education and Practice. 2014;5(5):61-71. Google Scholar

- Darrat M, Houlihan A, Gibson I, Rabbitt M, Flaherty G, Sharif F. Outcomes from a community-based hypertension educational programme: the West of Ireland Hypertension study. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2018 Aug;187(3):675-82.. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Yildiz E, Erci B. Effects of self-care model on blood pressure levels and self-care agency in patients with hypertension. Int. J. Health Sci. 2016 Mar;4:69-75. Google Scholar

- Hussein AA, Salam EA, Amr AE. A theory guided nursing intervention for management of hypertension among adults at rural area. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2016;7(1):66-78.

- Daniali SS, Eslami AA, Maracy MR, Shahabi J, Mostafavi-Darani F. The impact of educational intervention on self-care behaviors in overweight hypertensive women: A randomized control trial. ARYA Atheroscler. 2017 Jan;13(1):20-28. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Crouch R, Wilson A, Newbury J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of primary health education or intervention programs in improving rural women's knowledge of heart disease risk factors and changing lifestyle behaviours. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011 Sep;9(3):236-45. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Valles-Fernández R, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Mengual-Martínez L, Rosell-Murphy M, Prieto-De Lamo G, Martínez-Frutos F et al. Intervention for control of hypertension in Catalonia, Spain (INCOTECA Project): results of a multicentric, non-randomised, quasi-experimental controlled intervention study. BMJ Open. 2012 Apr 18;2(2):e000507. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Self-monitoring and other non-pharmacological interventions to improve the management of hypertension in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 Dec;60(581):e476-88. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ojo OS, Malomo SO, Sogunle PT, Ige AM. An appraisal of blood pressure control and its determinants among patients with primary hypertension seen in a primary care setting in Western Nigeria. South African Family Practice. 2016 Dec 9;58(6). Google Scholar

- Lee E, Park E. Self-care behavior and related factors in older patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Contemp Nurse. 2017 Dec;53(6):607-621. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sadeghi M, Shiri M, Roohafza H, Rakhshani F, Sepanlou S, Sarrafzadegan N. Developing an appropriate model for self-care of hypertensive patients: first experience from EMRO. ARYA Atheroscler. 2013 Jun;9(4):232-40. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Douglas BM, Howard EP. Predictors of self-management behaviors in older adults with hypertension. Advances in preventive medicine. Adv Prev Med. 2015;2015:960263. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Warren-Findlow J, Seymour RB, Shenk D. Intergenerational transmission of chronic illness self-care: Results from the caring for hypertension in African American families study. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):64-75. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Warren-Findlow J, Seymour RB, Brunner Huber LR. The association between self-efficacy and hypertension self-care activities among African American adults. J Community Health. 2012 Feb;37(1):15-24. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Katsinde C, Katsinde T. The Relationship between Reported Self-Care Practices and Blood Pressure Levels of Hypertensive Clients at a Provincial Hospital in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research (IJHSR). 2016;6(10):205-15. Google Scholar