Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality at Windhoek Central Hospital: an audit

Veparura Mutjavikua, Tinashe Portia Madziwazira, Kingsley Ufuoma Tobi

Corresponding author: Kingsley Ufuoma Tobi, Department of Surgical Sciences, Division of Anaesthesiology, Faculty of Health Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Hage Geongob Campus, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

Received: 10 Dec 2022 - Accepted: 29 Jan 2023 - Published: 10 May 2023

Domain: Obstetrics and gynecology

Keywords: Anaesthesia-related, maternal deaths, hospital, health care services, Namibia

©Veparura Mutjavikua et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Veparura Mutjavikua et al. Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality at Windhoek Central Hospital: an audit. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2023;12:5. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2023.12.5.38473]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/12/5/full

Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality at Windhoek Central Hospital: an audit

Veparura Mutjavikua1, Tinashe Portia Madziwazira1, ![]() Kingsley Ufuoma Tobi2,&

Kingsley Ufuoma Tobi2,&

&Corresponding author

Maternal death is a tragic but preventable problem worldwide. Anaesthesia as a cause of maternal death is reportedly low in developed countries; however, the incidence in developing countries is still not highlighted and is unknown in Namibia. The purposes of this study were to determine the maternal mortality ratio at Windhoek Central Hospital (WCH) as well as to evaluate anaesthesia-related maternal death. Maternal death cases from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020, were reviewed, and data on their type of delivery, cause of death, and variables associated with anaesthesia-related maternal death were extracted to determine the total contribution of anaesthesia to maternal death. A total of 40 maternal deaths were reviewed. The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) was less than 200 per 100,000 live births. Haemorrhage and eclampsia, and hypertensive disorders were the leading causes of death, with anaesthesia contributing to only 2% of deaths. Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality is 2% from this study. The anaesthesia-related death resulted from an adverse drug reaction of heavy marcaine. Other causes of maternal mortality included haemorrhage, eclampsia, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

It has been reported that up to 56% of maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Although the past 20 years have witnessed progress in ending preventable maternal death; we still have a long way to go. In 2014, Lihongeni and Indongo [2], in Namibia identified haemorrhage, eclampsia and puerperal sepsis as common direct causes, while HIV accounted for the commonest indirect cause. However, the study did not state the mode of delivery, whether vaginal or caesarean section. As a result, the role of anaesthesia in contributing to these maternal deaths could not be ascertained. In a similar study, Girum and Wasie [3], sought correlations between causes of maternal deaths and the maternal mortality ratio (MMR). The authors found a positive correlation with early marriage and total fertility per woman and crude birth rate. The study also found a relationship between high maternal death rates and the countries' socio-economic status, health care delivery system and disease burden. This finding echoes a previous study [2]. Kallianidis et al. [4] in a retrospective cohort study from 1999-2015, evaluated the risk of maternal deaths following both vaginal delivery and ceaseran-section (C-section). The study found that death following a C-section was 21.9 per 100 000 live births, whereas the deaths following vaginal delivery was 3.8 per 100 000 live births. Of all the 88 C-sections, 58 were primary/elective, and 28 were secondary. The authors concluded that C-sections carried a 3-fold increased risk of maternal death over vaginal delivery. Deaths directly related to anaesthesia were, however, not highlighted.

In 2016, Sobhy et al. [5] observed that the overall risk of death following anaesthesia was 1.2 per 1000 women, and 2.8% due to general anaesthesia. Administration of anaesthesia by non-physicians, especially those without formal training, was a significant risk factor for maternal deaths from anaesthesia. General anaesthesia resulted in a three-time greater risk of death compared to neuraxial anaesthesia. Management by non-physicians and physician anaesthetists carried a risk of death of 9.8 per 1000 and 5.2 per 1000 women, respectively. Specific anaesthetic causes identified included; airway complications (45%), staff competencies (27%), high spinal, drug overdose, and adverse drug effects, all causing 6 percent of maternal deaths due to anaesthesia. Enohumah and Imaregiaye [6] conducted a study to identify factors associated with anaesthesia-related maternal deaths. They reported 84 maternal mortalities among 12,394 deliveries occurred in the hospital during the period under review, a mortality rate of 678 per 1, 000, 000 deliveries. C-sections accounted for 2323 deliveries (18.7%). Infection, haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and anaesthesia were the leading causes of maternal mortality. Anaesthesia as the sole cause of six maternal deaths in this study, where the patients received general anaesthesia for the surgical procedure. Difficult airway, inadequate supervision of trainee anaesthetists and a lack of appropriate monitors were the primary anaesthetic reasons for these maternal deaths.

This was a retrospective, quantitative study of all maternal deaths at WCH from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020.

Inclusion criteria: forty maternal deaths, referring to women who died during childbirth, from pregnancy-related complications, or died within 42 days after childbirth, were included. Additional data on the total number of deliveries and C-sections carried out during the above time frame were retrieved from Matron records.

Exclusion criteria: pregnant women admitted to WCH where the outcome of the pregnancy was unknown were not included in the study.

Data collection tools: a data collection sheet was used to extract all relevant information from the patient's hospital records. Each sheet had a unique identification number with no other specific patient details to adhere to all ethical protocols. The data extracted included the hospital where the death occurred, whether the maternal death occurred following caesarean section or vaginal delivery, and the reported cause of death. Further information regarding the procedure was sought in cases of maternal death following caesarean section. Whether the death occurred intra-operatively or post-operatively, if the cause of death was identified as due to anaesthesia, the specific cause was documented.

Data entry and analysis: patients' information obtained from the data collection sheet was captured and coded into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Data obtained were cleaned and imported from the Excel spreadsheet and organized into graphs, tables and pie charts.

Ethical considerations: ethical approval for the conduct of the study was obtained from the Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS). The data collected contained no identifiable information and was used only for the study according to code of ethics.

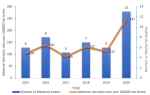

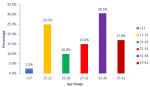

The MMR, calculated for each year, ranged from 104-247 per 100,000 live births (Figure 1). The largest proportion of maternal deaths occurred in women aged 32-36 years, 30.5% of deaths, followed by the age group 17-21 years, 25% of deaths (Figure 2). Haemorrhage was the largest contributor to all maternal deaths comprising 40% (6 deaths) while eclampsia and hypertensive disorders, accounted for 15% each. There was only one case of anaesthesia-related maternal death (2%) which was reported to be due to adverse drug reactions to the local anaesthetic, heavy marcaine (Figure 3). Table 1 shows the rate of C-section rate at WCH from 2015 to 2020. The highest rate of C-section was in 2018 (36.1%), followed by 33.3% in 2017. The result shows that 70% of the total C-sections were emergency. Regarding the type of anaesthesia performed for the C-sections, neuraxial anaesthesia accounted for 60% of the anaesthesia technique, while general anaesthesia made up the rest.

The MMR for WCH from 2015 to 2019 was less than 200/100, 000 live births, with a notable increase in 2020 with a higher MMR of 247/100, 000 live births. Similarly, in the USA, (11) in 2020, MMR was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births compared to 20.1 in 2019. This finding comes as a surprise, as one would have expected an improvement in MMR from 2015 to 2020. Some factors could however account for this, and one of these is the COVID-19 pandemic, which ravaged the world from 2019 to early 2022. Previously, maternal deaths have been found to increase with an increase in maternal age. In a report [7] by Hoyert, of the Division of Vital Statistics in the USA, MMR was 13.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for women under age 25 in 2020. The MMR for women aged 40 and above was 7.8 times higher than the rate for women under age 25. This contrasts with the findings of our study. We observed that the largest proportion of maternal deaths occurred in women aged 32-36 years, accounting for 30.5% of deaths. The older age groups 37-41 years made up 17% of maternal deaths. However, in order to accurately compare the relationship between maternal age and maternal deaths, the proportion of women in different age groups becoming pregnant must be considered.

The rate of C-sections from our study was 32.1% which is higher than the WHO recommendation of not more than 10-15% of births. According to the WHO, the rate of C-section continues to rise globally, and many C-sections are being performed for non-medical indications. Although the rate of C-sections is still low in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, it has been projected that by 2030, the highest rates are likely to be in Eastern Asia (63%), Latin America and the Caribbean (54%), Western Asia (50%), Northern Africa (48) Southern Europe (47%) and Australia and New Zealand (45%).” [8]. Previously, a study in Namibia [2] identified haemorrhage, eclampsia, and puerperal sepsis as the common direct causes of maternal death, while HIV accounted for the commonest indirect causes. Similarly, haemorrhage made up the commonest cause of maternal deaths in our study. A similar finding was observed in a study from Brazil by de Carvalho-Sauer et al. [9]. They reported that although some maternal deaths occurred due to a direct cause of COVID-19, even more deaths occurred due to haemorrhage.

The present study shows that 60% of the maternal deaths following C-section had neuraxial anaesthesia. In contrast, Sohby et al. [5], had reported that general anaesthesia increased the odds of maternal and perinatal deaths compared with neuraxial anaesthesia. Of all the maternal deaths recorded, only one death (2%) was directly attributed to anaesthesia, the specific cause being an adverse drug reaction. This is like the finding of a systematic review and meta-analysis by Sohby et al. who documented the rate of anaesthesia-related deaths to be 2-8%. The death attributed to anaesthesia in this study was due to an adverse drug reaction to heavy Marcaine. Previously, heavy Marcaine (Bupivacaine) had been associated with a rare but lethal adverse effect following intrathecal administration [10]. Although, the exact mechanism of this complication is unknown; however, it might have resulted from systemic absorption of high doses or cephalic spread of the drug.

Anaesthesia contributed to 2% of maternal deaths at WCH between 2015-2020. Other causes of maternal deaths highlighted include haemorrhage and hypertensive disease and eclampsia comprising the majority.

What is known about this topic

- Maternal mortality is high in sub-Saharan Africa, like Namibia;

- Haemorrhage, sepsis and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are some of the common direct causes of maternal deaths.

What this study adds

- No study has been conducted in Namibia to the best of our knowledge on the contribution of anaesthesia to maternal death; this study therefore highlighted that anaesthesia contributed about 2% to maternal deaths at Windhoek Central Hospital.

The authors declare no competing interests.

All the authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

Table 1: rate of caesarean caesarean sections at WCH from 2015 to 2020

Figure 1: maternal mortality ratio: trend of maternal death rates from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020

Figure 2: age distribution of maternal deaths

Figure 3: specific causes of maternal death after C-sections

- National Research Council, Committee on Population. The Consequences of Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality: Report of a Workshop. National Academies Press; 2000 Apr 21. Google Scholar

- Lihongeni M, Indongo N. Causes and risk factors of maternal deaths in Namibia. Journal for Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences. 2014 Nov 18:242-52. Google Scholar

- Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017 Nov;3(1):19. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kallianidis AF, Schutte JM, Roosmalen JV, Akker TV. Maternal Mortality After Cesarean Section in the Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74(3):139-41. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sobhy S, Zamora J, Dharmarajah K, Arroyo-Manzano D, Wilson M, Navaratnarajah R et al. Anaesthesia-related maternal mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 May;4(5):e320-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Enohumah KO, Imarengiaye CO. Factors associated with anaesthesia-related maternal mortality in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006 Feb;50(2):206-10. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Donna L. Hoyert. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020. 2020. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Jun;6(6):e005671. PubMed | Google Scholar

- de Carvalho-Sauer RCO, Costa MDCN, Teixeira MG, do Nascimento EMR, Silva EMF, Barbosa MLA, da Silva GR et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on time series of maternal mortality ratio in Bahia, Brazil: analysis of period 2011-2020. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Jun 10;21(1):423. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wolfe RC, Spillars A. Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: Reviewing Updates From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Practice Advisory. J Perianesth Nurs. 2018 Dec;33(6):1000-5. PubMed | Google Scholar