Bipolar disorder among patients attending mental healthcare clinic in war-tone settings of the Democratic Republic of Congo: a hospital-based study

Franck Muyisa Visondwa, Rock Kasereka Masuka, Junior Paluku Kasomo, Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya

Corresponding author: Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya, Department of Psychiatry, Kampala International University Western Campus, Ishaka, Uganda

Received: 05 Nov 2023 - Accepted: 25 Jan 2024 - Published: 30 Jan 2024

Domain: Epidemiology, Non-Communicable diseases epidemiology, Psychiatry

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, factors associated, Democratic Republic of Congo, conflict zones

©Franck Muyisa Visondwa et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Franck Muyisa Visondwa et al. Bipolar disorder among patients attending mental healthcare clinic in war-tone settings of the Democratic Republic of Congo: a hospital-based study. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2024;14:14. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2024.14.14.42124]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/14/14/full

Research

Bipolar disorder among patients attending mental healthcare clinic in war-tone settings of the Democratic Republic of Congo: a hospital-based study

Bipolar disorder among patients attending mental healthcare clinic in war-tone settings of the Democratic Republic of Congo: a hospital-based study

![]() Franck MuyisaVisondwa1, Rock Kasereka Masuka1, Junior Paluku Kasomo2,

Franck MuyisaVisondwa1, Rock Kasereka Masuka1, Junior Paluku Kasomo2, ![]() Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya3,&

Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya3,&

&Corresponding author

Introduction: while bipolar disorder is among the main causes of admissions to mental health facilities, few studies have assessed its burden among patients seeking care in mental hospitals in conflict zones. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of bipolar disorder and its correlates among patients seeking healthcare services in two mental hospitals located in conflict zones of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Methods: between January and December 2018, 1025 patients seeking healthcare at two mental hospitals located in conflict zones of the DRC were screened for bipolar disorder using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Descriptive analyses were performed to determine information on prevalence rates of bipolar disorder, while inferential analyses were used to determine factors associated with bipolar disorder.

Results: one in ten mentally ill patients seeking healthcare at mental hospitals in conflict zones met the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, with a significant proportion having bipolar II disorder. The factors associated with bipolar disorder among patients seeking healthcare services in two mental health facilities located in conflict zones of DRC are being male, 30 years old or older, living in an urban setting, and having a family history of mental disorders.

Conclusion: bipolar disorder is highly prevalent in patients attending mental health facilities in the conflict zones of the DRC. Early detection of bipolar disorder among patients with mental disorders living in conflict settings should be based on their socio-demographic profile, especially their gender, age, address, and family history of psychiatric illness.

While bipolar disorder is among the main causes of admissions to mental health facilities [1], its burden remains unknown among patients seeking care in mental hospitals in conflict zones. Traumatic events secondary to combat exposure are associated with significant psychological distress, leading to or complicating several mental disorders linked to exposure to traumatic events, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mood disorders [2]. A large body of literature showed a correlation between exposure to war-related trauma and prevalence rates of mood disorders [3-6]. Up to 20% of readmissions to mental health facilities are caused by recurrent episodes of bipolar disorder and associated comorbidities [7,8]. To date, there is a paucity of data on the proportion of patients with bipolar disorder receiving treatment in mental health facilities located in conflict zones of developing countries, where there is poor screening for bipolar disorders [7] and impaired quality of life among patients with bipolar disorders [9], given the lack of trained mental health providers [10].

Although combat exposure-related trauma is among the main contributors to mental health problems in conflict zones, several factors intervene to cause bipolar disorder. These factors included not only age, gender, substance abuse, childhood trauma, and genetic predisposition but also clinical history [5,6,8]. The likelihood of bipolar disorder has been shown to increase in individuals with these factors who live in conflict zones. Recent evidence revealed that up to 2 in 10 patients in conflict settings have mood disorders [3,11]. A study carried out in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) revealed that exposure to armed conflict and unstable socioeconomic situations results in more likely affective disorders than psychotic disorders [5]. However, this study did not specify the type of bipolar disorder commonly found in survivors of armed conflict. The eastern part of the DRC has been affected by armed conflict for more than two decades. Although its communities present common figures of living in conflict zones like poverty, displacement, and health inequalities, this region lacks trained mental health specialists, making the majority of patients treated by general practitioners with a high chance of misdiagnosing mental health problems [10]. This study, aiming to provide preliminary data, is part of a project targeting the development of appropriate measures that may allow early detection of psychiatric disorders in both specialized and primary healthcare settings. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of bipolar disorder and its correlates among patients seeking healthcare services in two mental health facilities located in conflicting areas of the DRC.

Study design: this was a cross-sectional study employing a quantitative approach.

Study setting: this study involved participants recruited from patients attending healthcare services at the two hospitals of the Cepima mental health center, located in Butembo City, North-Kivu province, in the eastern DRC. Cepima is involved in managing almost all the patients with neuropsychiatric disorders living in Butembo City, in North-Kivu province, DRC, which has been affected by armed conflicts for more than two decades [5,10]. These facilities organized both outpatient and inpatient services, with an average of 20 outpatients and 40 inpatients daily for each hospital. The common mental illnesses at these hospitals are substance use-related problems, bipolar affective disorder, PTSD, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, epilepsy, and major depressive disorders.

Participants: we included all adult (aged 18 and older) patients attending the above-mentioned mental hospitals, living in conflict areas in the past five years, having recovered and being fully aware of their illness, and providing written informed consent or whose caregiver provided assent. Exclusions were patients with manic or depressive symptoms related to substance use disorders, schizophrenic spectrum disorders, PTSD, or any medical or psychiatric co-morbidities. These exclusions were established to minimize the overlap of mood disorders, which may impair the interpretation of the study findings.

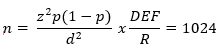

Sample size determination: we estimated the sample size using the modified Daniel´s formula [12], while using the bipolar disorder prevalence (p) estimated at 5.2% in mental health facilities [5] a design effect (DEF) of 2, an overall minimal rate of 90% to adjust the sample size for non-response, and a precision of 2% (d, relative standard error). At a 95% confidence level (z = 1.96) and a sampling error of 10%, the minimal sample size (n) was:

Procedures: this study used a purposive sampling method by including all adult patients seeking healthcare services at the two hospitals of the Cepima Mental Health Center between January and December 2018. We collected data through consecutive recruitment and face-to-face interviews. Participants who were inpatients and outpatients seeking care in the selected mental hospitals were approached and asked to provide written informed consent to participate in this study after receiving details about the study from the research assistants. The research assistants checked their records, searching for those fulfilling the inclusion criteria. All the potential participants were given a detailed language summary of the study objectives and procedures, after which those who provided information were interviewed. After giving consent, participants were administered a questionnaire by trained research assistants. Each interview took about 35 to 45 minutes. Potential participants with active symptoms in an outpatient clinic were reviewed once they were stable in inpatient units.

Variables: data was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire established based on socio-demographic characteristics, clinical factors, and psychiatric diagnosis. The independent variables included information on socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, level of education, and address. We also collect data on the family history of psychiatric illness. The outcome variable was bipolar disorder, assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), version 7.0, based on the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria [13]. Regarding mental disorders, we counted the number of symptoms presented by the participants. We took the psychiatric diagnosis that the patients were treated for from the medical records and confirmed it using the MINI.

Quality control: questionnaires were checked for completeness, pretested on five inpatients and five outpatients not included in the analyses reported in this study, and administered consecutively. All data collection tools were written in French, translated into Swahili, and back-translated into French in an iterative process to ensure translation fidelity. Depending on the participants´ preferences, interviews were conducted in Swahili or French. For accuracy, two research assistants and the first author assessed the questionnaire in French and Kiswahili.

Statistical analyses: statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive statistics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and medians for continuous variables. Inferential analyses using linear logistic regression were performed to determine factors associated with bipolar disorder. The threshold of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Ethical considerations: before data collection, all study protocols received approval from the Academic Board of the Faculty of Medicine at the Catholic University of Graben (DRC). Permissions for carrying out the study were obtained from the chairman of the health zone in Butembo and the executive director of the Cepima Mental Health Center. The study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants or their caregivers provided written informed consent or assent.

Baseline information: in total, 1025 patients attended healthcare at the Cepima mental health centers. The majority of them were males, with a mean age of 26.3 (SD = 7.1) years, lived in rural areas, and had a positive family history of psychiatric illness.

Prevalence of bipolar disorder in patients seeking healthcare at mental hospitals located in conflict zones: one hundred fourteen patients (11.1%) met the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, among which 61 patients (53.5%) met the diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

Factors associated with bipolar disorder in patients seeking healthcare at mental hospitals located in conflict zones: most of the participants with bipolar disorders were 30 years old, male, single or separated, had never studied, and had a family history of mental disorders. The mean age of participants at their first episode was 18.4 (SD = 2.9) years. We also found that patients who were male, 30 years of age and older, lived in an urban setting, and had a family history of mental disorders were less likely to be associated with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Table 1).

This study presents preliminary findings on the burden of bipolar disorder on psychiatric admissions at two mental hospitals in conflict zones of the DRC. Its findings provide an update on psychiatric research in settings where there is a lack of studies, which may serve as a starting point for further studies. The results indicating that 11.1% of patients attending mental facilities in conflict settings had bipolar disorder support other research [11,14,15]. Living in conflict settings is a significant psychosocial factor that is associated with several psychiatric disorders, especially post-traumatic stress disorder and mood disorder [3,6,10]. In such settings, important attention is focused on trauma and stress-related disorders, whereas patients with mood disorders, whether they fulfill the criteria of bipolar disorder or not, lack proper management in most cases [5, 8,16]. We also found that the majority of participants had bipolar II disorder. This result aligns with the study carried out by Vivalya and associates in the same setting [5]. Depressive episodes are commonly found in conflict zones, compared to manic episodes.

Conversely, studies showing differences in gender distribution in bipolar disorder [2], our findings showed that the majority of patients were male in mental hospitals located in conflicting regions. Longstanding stress contributed equally to mental health problems in both males and females in the aftermath of armed conflict [4,17]. Another consideration in interpreting our findings is that the majority of participants were 30 years old or older. This finding is divergent from previous studies, indicating that the majority of patients with bipolar disorder are young [1,2]. The discrepancy can be explained by the fact that this study was carried out in a conflict zone, which may trigger a mood episode, regardless of their genetic predisposition. Similar to existing studies indicating that their first episode of psychiatric disorder, including bipolar disorder, occurs between 15 and 24 years old [4,18], the majority of our patients had their episode at the age of 18.4 (SD = 2.9) years. We recommend that a proper assessment of bipolar disorder be systematically performed among adults attending mental health facilities located in conflict zones.

We also found that the majority of psychiatric patients with bipolar disorder in conflict zones are from rural settings. Armed conflict is commonly reported in rural areas, where rebels are present. However, displaced communities from insecure regions to cities poorly report health-related issues in the settlement, especially if these challenges are not causing distress to others, such as depression, which is common in rural settings [3,6,11]. Moreover, our study revealed that the majority of participants had a family history of psychiatric disorders. A genetic contribution to the occurrence of bipolar disorder has been reported in numerous studies, regardless of whether one lives in or is not in conflict zones [8]. Our study´s findings must be interpreted in the context of the following limitations: First, this study is a point-proportional study of those with bipolar disorder attending two mental health clinics located in conflict settings in the DRC. Second, this study was a hospital-based sample, which is not representative of the general community but describes the characteristics of the study participants; hence, its results may not be generalized to the community population. Third, using the MINI scale translated into the local language (Kiswahili) could impair the participant´s response and scoring. Extensive studies should be conducted in the community based on specific sample size calculations and random sampling techniques.

Our results demonstrated that one-tenth of patients attending mental health facilities in conflict regions of the DRC had bipolar disorder. We found that bipolar II disorder is more likely common than bipolar I disorder in patients seeking healthcare in mental hospitals in conflict zones. Furthermore, the findings showed that the majority of patients with bipolar disorder had a family history of mental disorders and were older than 30 years old. Early detection of bipolar disorder among patients with mental illnesses in settings of armed conflict should be based on their socio-demographic profile.

What is known about this topic

- Living in conflict zones is associated with several mental health challenges, including bipolar disorder;

- Bipolar disorder is among the main causes of hospital admissions to mental facilities.

What this study adds

- One-tenth of patients attending mental health facilities in conflicting regions had bipolar disorder;

- Early detection of bipolar disorder among patients with mental illnesses in armed conflict region settings should be based on their socio-demographic profile.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Franck Muyisa Visondwa designed the study and collected data. Rock Kasereka Masuka searched for literature. Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya and Junior Paluku Kasomo revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript before submission for publication.

We acknowledge our study participants for the time they committed to be part of this study. Bives Mutume Nzanzu Vivalya would like to thank MicroResearch International Canada and Academic without Borders for his training in scientific research and graduate research supervision and mentorship, respectively.

Table 1: bipolar disorder and its correlates among patients seeking care at Cepima mental health center

- Clemente AS, Diniz BS, Nicolato R, Kapczinski FP, Soares JC, Firmo JO et al. Bipolar disorder prevalence?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015 Apr-Jun;37(2):155-61. PubMed| Google Scholar

- Bowden CL. A different depression: Clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2005 Feb;84(2-3):117-25. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019 Jul 20;394(10194):240-248. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Trujillo S, Giraldo LS, López JD, Acosta A, Trujillo N. Mental health outcomes in communities exposed to Armed Conflict Experiences. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):1-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Vivalya BM, Bin Kitoko GM, Nzanzu AK, Vagheni MM, Masuka RK, Mugizi W et al. Affective and Psychotic Disorders in War-Torn Eastern Part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychiatry J. 2020 Jul 24:2020:9190214. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hoppen TH, Priebe S, Vetter I, Morina N. Global burden of post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression in countries affected by war between 1989 and 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Jul;6(7):e006303. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Stang P, Frank C, Yood MU, Wells K, Burch S. Impact of bipolar disorder: Results from a screening study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(1):42-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Rowland TA, Marwaha S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018 Apr 26;8(9):251-269. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sylvia LG, Montana RE, Deckersbach T, Thase ME, Tohen M, Reilly-Harrington N et al. Poor quality of life and functioning in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017 Dec;5(1):10. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mutume B, Vivalya N, Vagheni MM, Manzekele G, Kitoko B, Vutegha JM et al. Developing mental health services during and in the aftermath of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in armed conflict settings?: a scoping review. Global Health. 2022 Jul 14;18(1):71. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mental GBD, Collaborators D. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-50. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Viechtbauer W, Smits L, Kotz D, Budé L, Spigt M, Serroyen J et al. A simple formula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015 Nov 1;68(11):1375-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Cooper R. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM). Knowl Organ. 2017;44(8):668-76. Google Scholar

- Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, Perugi G, Vieta E, Gamma A et al. Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed bipolar disorders in patients with a major depressive episode: The BRIDGE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Aug;68(8):791-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Maxwell V, Hale S, Lam RW. The impact of bipolar disorder upon work functioning: A qualitative analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2007 Feb-Mar;9(1-2):126-43. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Khoury L, Tang YL, Bradley B, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an urban civilian population. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(12):1077-86. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Gitlin M, Malhi GS. The existential crisis of bipolar II disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020 Jan 28;8(1):5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- McIntyre RS, Berk M, Brietzke E, Goldstein BI, López-Jaramillo C, Kessing LV et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet. 2020 Dec 5;396(10265):1841-1856. PubMed | Google Scholar