Camurati-Engelmann bone dysplasia diagnosed fortuitously after a road traffic accident: a case report

Joshua Tambe, Sylviane Dongmo, Jean-Roger Mouliom, Pierre Ongolo-Zogo

Corresponding author: Joshua Tambe, Division of Radiology, Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Received: 11 Jan 2021 - Accepted: 18 Jan 2021 - Published: 28 Jan 2021

Domain: Radiology,Internal medicine

Keywords: Camurati-Engelmann, bone dysplasia, case report

©Joshua Tambe et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Joshua Tambe et al. Camurati-Engelmann bone dysplasia diagnosed fortuitously after a road traffic accident: a case report. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2021;5:40. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2021.5.40.27811]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/5/40/full

Case report

Camurati-Engelmann bone dysplasia diagnosed fortuitously after a road traffic accident: a case report

Camurati-Engelmann bone dysplasia diagnosed fortuitously after a road traffic accident: a case report

![]() Joshua Tambe1,2,&, Sylviane Dongmo1,2, Jean-Roger Mouliom3, Pierre Ongolo-Zogo4

Joshua Tambe1,2,&, Sylviane Dongmo1,2, Jean-Roger Mouliom3, Pierre Ongolo-Zogo4

&Corresponding author

Camurati-Engelmann bone dysplasia is a rare genetic disease characterized by craniotubular hyperostosis. The radiological features are often characteristic and sufficient for diagnosis. Being a rare condition it can be unknown to some healthcare professionals and thus remain undiagnosed. We report a case diagnosed fortuitously whilst performing imaging following trauma.

Camurati-Engelmann disease (CED) is a rare autosomal dominant bone dysplasia that typically affects the diaphysis of the long bones and the skull. Radiologically it is characterized by craniotubular hyperostosis with thickening of the endosteum and the periosteum of the cortical bone [1]. It can extend to the metaphyses but usually spares the epiphyses [1-3]. At the skull there is often cortical bone sclerosis and thickening with obliteration of the diploic spaces. The common clinical manifestations include a waddling gait, limb pain, muscular weakness and fatigue [2,4,5]. Depending on the extent of skull involvement patients can complain of headaches, hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, and vision problems. Imaging findings can be sufficient to make a diagnosis of CED [3,4]. Bone scintigraphy is useful to determine the extent of the disease. Molecular genetic testing reveals mutations in the transforming growth factor β1 gene (TGF-β1) [6]. The treatment is symptomatic with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and losartan to relief pain and slow disease progression, though decompression surgery can be performed when there are severe neurological deficits [4,7-10]. Two cases have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa [11,12] with none so far from Cameroon. Given the rarity of CED it might be unknown to some healthcare professionals and therefore remain undiagnosed. People affected may also not readily seek care due to socio-cultural and economic barriers. We report a case diagnosed fortuitously during radiological investigations indicated for trauma following a road traffic accident.

A 37-year old male patient was rushed to the Emergency Department (ED) of Regional Hospital Limbe after a road traffic accident. He was allegedly knocked down by a moving vehicle while crossing the road and suffered initial loss of consciousness. He reportedly regained consciousness some minutes later while being transported to the hospital. On arrival at the ED he was conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15 and his vital signs were stable. He could move his limbs, walk by himself and only complained of headaches. There were no bruises. However, there was proptosis and some focal swellings were observed on the calvarium and right distal forearm. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and a radiograph of the right forearm were requested. Symptomatic treatment was given with the administration of stat doses of the opioid analgesic Tramadol (subcutaneous injection of 50mg) and the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug Diclofenac (intramuscular injection of 75mg). CT was performed with a 16-slice scanner (HITACHI Supria©). The patient was positioned head-first and supine on the motorized table and scanning was caudo-cephalic from the thoracic inlet to the vertex. Data acquisition was volumetric with a pitch of 1.0625, collimation of 0.625 x 16, reconstruction index of 0.75mm, a peak tube voltage of 120kV and a modulated tube current between 263mA and 350mA. Post-processing imaging techniques included bone windowing, multiplanar reformatting and three-dimensional volume rendering. For the forearm radiograph two orthogonal views were obtained.

The radiographic and CT images were consistent with a diagnosis of CED (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6). There was no traumatic lesion on these studies. The ED physician was informed of the findings and the patient was reassured there was no brain injury. The patient was further interviewed and examined by the first author. He was admitted because of intermittent headaches and feeling his body very “heavy” in recent years and so moves at a slow pace. Also, he stated that he encounters difficulties crossing the road as he cannot turn fast enough to look to the left and subsequently to the right before doing so. He reported not seeking care for these complaints as his main economic activity was not perturbed. His physical built-up was different from his siblings and people often looked at him intently making him feel “different” or “strange”. After consultation with an endocrinologist, thyroid-stimulating hormone and parathormone assays were normal. The full blood count revealed mild anemia. Consultations at the eye clinic further revealed myopia requiring optical correction. The patient was counseled on the hereditary nature of the diagnosis and placed on an oral hematinic and corticosteroid (prednisolone). He reported feeling well one month after leaving the hospital. He was scheduled for routine follow-up visits and advised to seek care anytime the need arose.

The onset of CED is usually during childhood and before 30 years of age [1,2,4]. Delayed diagnosis is likely if people affected do not seek care or if healthcare providers do not investigate symptoms appropriately or fail to recognize them. Not seeking care can be due to stigma as a result of the community perception of the skeletal deformities, ignorance, and the lack of the financial means. If the local sociocultural perception of such conditions attribute it to mysterious causes then people who are affected are at risk of social exclusion. For the case we report the skeletal deformities were initially attributed to trauma. This is a “satisfaction of search” bias given the clinical context. The decision to explore with imaging however led to the diagnosis. The patient´s underlying condition (CED) predisposed to the accident even though the road conditions and the attitude of the driver probably also contributed.

The quasi-complete obliteration of the bone medullary cavity as seen on the radiograph can explain the anemia [13]. Extensive sclerosis at the skull base with thickening progressively narrows the orifices with potential for cranial nerve impingement. There was already a grade III exophthalmos and blindness would be a threat if the disease progresses rapidly and obliterates the optic canal. Hearing impairment, tinnitus and vertigo are expected complications given the extensive sclerosis of the petrous segment of the temporal bones with narrowing of the internal auditory canals. The markedly hyperostotic mandibles would also pose a threat to mastication. The clinical course and disease progression are variable. Some authors have reported a favorable outcome after medical treatment with pain relief and improved exercise capacity [7,9,10]. Psychosocial support is also necessary to facilitate acceptance and social inclusion.

Ethics: no experiments were performed on the patient. The cost of the laboratory assays, endocrinology and ophthalmology visits were borne by the health facility as the patient could not afford. The authors obtained the consent of the patient for this report. No data to directly identify the patient is present in this article.

Limitations: bone scintigraphy to determine the extent of involvement for classification was not done given that the technology was not geographically accessible. Also molecular genetic testing was not done for the definitive diagnosis, however the CT and radiographic findings were sufficiently pathognomonic.

Camurati-Engelmann disease (CED) is rare and the radiological features are characteristic and often sufficiently diagnostic. The reporting of cases would create awareness among healthcare professionals who are expected to encourage patients to seek care early and provide them with the necessary counsel and support.

The authors declare no competing interests.

JT analyzed the images, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. SD and JRM reviewed the images and contributed to drafts of the manuscript. POZ corrected the final version of the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

The authors thank the patient for consenting that the case be reported.

Figure 1: CT scannogram. Hyperostotic calvarium (long arrows), mandibles (short arrows) and sclerotic skull base with sclerosis of C1 and C2 vertebrae (arrow heads)

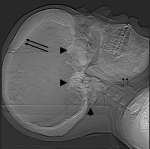

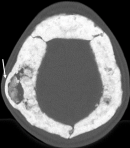

Figure 2: axial CT depicting exophthalmos. There is sclerosis and thickening of the skull base. Both eyeballs are anterior to the bicanthal plane (arrow) corresponding to grade III exophthalmos

Figure 3: axial CT of the calvarium. There is sclerosis and thickening of the calvarium with obliteration of the diploic spaces. Focal right parietal diploic widening (arrow)

Figure 4: 3D volume rendered CT of the skull. Focal bumps of the calvarium (arrows) and hypertrophied mandible (arrow head)

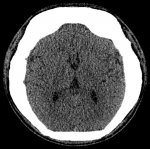

Figure 5: axial CT of the brain. This section through the foramen of Monroe shows normal brain parenchyma

Figure 6: right forearm radiograph. There is symmetrical cortical hyperostosis with quasi-complete obliteration of the medullary cavity at the diaphysis and metaphyses

- Vanhoenacker FM, Janssens K, Van Hul W, Gershoni-Baruch R, Brik R, De Schepper AM. Camurati-Engelmann Disease. Review of radioclinical features. Acta radiol. 2003;44(4):430-434. PubMed | Google Scholar

- de Bonilla Damiá Á, García Gómez FJ. Camurati-Engelmann Disease. Reumatol Clínica. 2017;13(1):48-49. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Restrepo JP, Molina M del P. Camurati-Engelmann disease: case report and review of literature. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23(3):218-222. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Janssens K, Vanhoenacker F, Bonduelle M, Verbruggen L, Van Maldergem L, Ralston S et al. Camurati-Engelmann disease: review of the clinical, radiological, and molecular data of 24 families and implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Med Genet. 2005;43(1):1-11. Google Scholar

- Van Hul W, Boudin E, Vanhoenacker FM, Mortier G. Camurati-Engelmann disease. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019;104(5):554-560. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Janssens K, Gershoni-Baruch R, Guañabens N, Migone N, Ralston S, Bonduelle M et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the latency-associated peptide of TGF-β1 cause Camurati-Engelmann disease. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):273-275. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bourantas K, Tsiara S, Drosos AA. Successful treatment with corticosteroid in a patient with progressive diaphyseal dysplasia. Clin Rheumatol. 1995;14(4):485-486. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Allen DT, Saunders AM, Northway Jr. WH, Williams GF, Scafer IA. Corticosteroids in the treatment of Engelmann´s disease: progressive diaphyseal dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1970;46(4):523-531. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kim YM, Kang E, Choi JH, Kim GH, Yoo HW, Lee BH. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in Camurati-Engelmann disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(14):e0309. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ayyavoo A, Derraik JGB, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL. Elimination of pain and improvement of exercise capacity in Camurati-Engelmann disease with Losartan. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):3978-3982. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Byanyima RK, Nabawesi JB. Camurati-Engelmann´s disease: a case report. Afr Health Sci. 2002;2(3):118-120. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mwasamwaja AO, Mkwizu EW, Shao ER, Kalambo CF, Lyaruu I, Hamel BC. Camurati-Engelmann disease: a case report from sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford Med Case Reports. 2018;2018(7). PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ghosal SP, Mukherjee AK, Mukherjee D, Ghosh AK. Diaphyseal dysplasia associated with anemia. J Pediatr. 1988;113(1):49-57. PubMed | Google Scholar