Prevalence and associated factors of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi, in the south of Democratic Republic of Congo: situation in 2020

Chola Mwansa Joseph, Mwembo Tambwe Albert, Tamubango Kitoko Herman, Ngwe Thaba Jules, Kakoma Sakatolo Zambèze, Kalenga Muenze Kayamba Prosper

Corresponding author: Chola Mwansa Joseph, Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

Received: 12 Feb 2021 - Accepted: 24 Nov 2021 - Published: 06 Dec 2021

Domain: Obstetrics and gynecology

Keywords: Anemia, pregnancy, prevalence, associated factors, Lubumbashi

©Chola Mwansa Joseph et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Chola Mwansa Joseph et al. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi, in the south of Democratic Republic of Congo: situation in 2020. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2021;7:19. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2021.7.19.28351]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/7/19/full

Case series

Prevalence and associated factors of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi, in the south of Democratic Republic of Congo: situation in 2020

Prevalence and associated factors of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi, in the south of Democratic Republic of Congo: situation in 2020

Chola Mwansa Joseph1,&, ![]() Mwembo Tambwe Albert1,2, Tamubango Kitoko Herman1, Ngwe Thaba Jules1,

Mwembo Tambwe Albert1,2, Tamubango Kitoko Herman1, Ngwe Thaba Jules1, ![]() Kakoma Sakatolo Zambèze1, Kalenga Muenze Kayamba Prospe1,3

Kakoma Sakatolo Zambèze1, Kalenga Muenze Kayamba Prospe1,3

&Corresponding author

Anemia during pregnancy is still a topical scientific question and a major public health problem, especially in countries with limited resources. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi and to identify the associated factors. This is a retro-prospective cross-sectional descriptive study carried out over 5 years in the city of Lubumbashi and its surroundings. Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level below 11 g/dl. For the retrospective part, we used a collection sheet which recruited any pregnant woman who consulted in one of the health structures during the period of the study and in whom the hemoglobin dosage was made at the using the HemoCue technique. The different variables collected were analyzed in relation to the anemia considered as the independent variable. Univariate analysis was done and logistic regression was also performed in order to determine the associated factors. For the prospective part, CYANHEMATO was used to analyze the blood in order to see if the situation has changed. Concerning the retrospective study, 2400 patients were selected. Concerning the prospective study, 128 patients of whom 52 were of low income and 76 of high income were selected. In view of the retrospective study, the prevalence of anemia in Lubumbashi was around 52.8% (n=1267). The Hb means decreased as the pregnancy progressed. It was 10.5 in the first trimester and reached 9 in the third trimester, passing by 9.8 in the second trimester. The associated factors for anemia were a large family (aOR 1.30, 95% CI 1.09-1.54; p=0.003); living in a rural area (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.20-1.42; p=0.0001) and malaria (aOR 1.95, 95% CI 1.54-2.31; p=0.0001). The prospective study carried out in the third trimester in late 2020 showed that, depending on the income of the population, four out of five (n= 44) and two out of five (n=32) pregnant women were anemic in the population of low and high income respectively. Hemoglobin averages were 9.63±1.52 and 11.19±1.07 g/dl in the low and high income population in the third trimester of pregnancy, respectively. Anemia in pregnant women in Lubumbashi is a reality, it affects two to four pregnant women out of five. It requires actions of good management and prevention strategies.

Anemia in pregnant women remains a major public health concern around the world to this day. However, its prevalence varies from country to country, region to region, or continent to continent. In each of these regions, it is multifactorial. According to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, anemia in pregnancy is defined as a hemoglobin level <11g/l. The prevalence of anemia is an important health indicator. A 2013 study showed that anemia is more prevalent in developing countries (43%) than in developed countries (9%). Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy varies among women with different socio-economic conditions, lifestyles or health behaviors across cultures [1].

Anemia in pregnancy is associated with several factors. It is associated with an age below 20 years, advanced age of pregnancy, high plasmodium parasitaemia and geophagy [2]. Twenty years ago, in Lubumbashi, a prevalence of 50 to 80% was discovered and anemia in pregnant and lactating women was associated with malaria and helminthiasis [3]. The causes of anemia during pregnancy in developing countries are multifactorial; these include micronutrient deficiencies of iron, folic acid and vitamins A and B12 and anemia due to parasitic infections such as malaria and hookworm or chronic infections such as tuberculosis and HIV. The contributions of each of the factors that cause anemia during pregnancy vary depending on geographic location, dietary practices and season. But in sub-Saharan Africa, insufficient intake of iron-rich diets is reported to be the leading cause of anemia in pregnant women [4,5]. Maternal anemia is associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death and low birth weight. The risks increased with simultaneous anemia and underweight [6].

Indeed, knowledge of the extent of the problem and its associated factors can lead to guidance in strategies for the fight and prevention of this pathology during pregnancy. This study aimed at the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy and at the identification of the associated factors.

Study design and setting

This study has a retrospective and a prospective component. Regarding the retrospective study, it is a cross-sectional descriptive study, the data of which were collected retrospectively from 2015 to 2019. We used a collection sheet which recruited any pregnant woman who consulted in one of the health structures during the period of the study and in which the hemoglobin assay was done using the HemoCue technique. Regarding the prospective study performed in october 2020, it was a cross-sectional descriptive observational study carried out in Lubumbashi on pregnant women who came for third trimester prenatal consultations in apparent good health. Several maternities were included in this work: they are the maternity unit of the university clinics of Lubumbashi, the General Provincial Hospital of Reference Jason Sendwe, the polyclinic of Des Oliviers, the salama organization and the Clinic Sainte Bernadette.

Study population

The retrospective study was conducted over the entire extent of the city of Lubumbashi, from the outskirts to the center. Several health axes were considered, these are the health ax Kafubu, Ruashi Zambia, ax Likasi, ax Kasapa, ax Kenya-Katuba, ax Kinsanga-Kasumbalesa. Data collection was concentrated in rural centers in the first three axes and in urban centers in the other axes. In each axes, the health structures in which we could measure hemoglobin using Hemocue in pregnant women were selected. We selected 1200 patients in rural axes and 1200 patients in urban axes. Concerning the prospective study, 128 patients of which 52 were of low income and 76 of high income were selected.

Data collections

Concerning the retrospective study, the sample size was calculated based on a prevalence of around 50% described in several national family health surveys [7]. Using Cochrane's formula [8],

Z = score which corresponds with 95% to 1.96; p = prevalence of anemia (50% = 0.5); q = proportion of pregnant non-anemic pregnant women (1-0.5 = 0.5); d = 5% margin of error (0.05), a sample size of 385 pregnant was found. Thus, around 600 pregnant women were collected in each health axis, which gives 3600 pregnant women across the city of Lubumbashi. After eliminating incomplete records, 2400 patients were included in the study. For each pregnant woman included in the study, socio-demographic parameters such as age, marital status, profession, residence; anthropometric parameters, weight and height; obstetric variables such as age of pregnancy when measuring hemoglobin, parity, pregnancy, previous abortions, previous deaths, previous premature births, previous low birth weights, age of pregnancy during the first consultation, pathologies associated with pregnancy, prescription of supplementation. The collected sheet was pre-tested in each of these structures before being validated for the study. Concerning the prospective study, the pregnant women were divided into two groups according to the income. These are the low the high income. There were 52 patients of low income and 76 patients of high income; a total of 128 pregnant women. All pregnant women who presented with complaints or pathologies on admission were excluded from the study. This is the case with hypertension in pregnancy, bleeding in the third trimester and or febrile illnesses. Pregnant women in whom the hematological data were not included, they were excluded from the study.

Definitions

Regarding the hemoglobin (Hb) level, the pregnant woman with an Hb level of less than 11g/dl was considered to be anemic. The anemia was also divided into three sections according to the WHO: Hb (g/dl) between 10 and 10.9, it was mild anemia; between 7 and 9.9 it was moderate anemia and below 7 it was severe anemia [9]. Regarding the socio-economic level, three classes were defined: the low level (less than 100 USD of monthly income), the medium level (101-499 USD of monthly income) and the high level (more than 500 USD monthly income). This breakdown was taken from the EDS survey [10]. CYANHEMATO was used to analyze blood by Coulter's technique, which consists of counting cells passing through an orifice and measuring the hemoglobin content of red blood cells by photometry. Regarding the age of the patients, two groups were formed, the one that was below 18 years old and the one that started at 18 years and above. Indeed, motherhood under 18 is very risky

Statistical analysis

Data was recorded using Excel software and processed with SPSS. The prevalence of anemia was defined by the proportion of anemic pregnant women among all pregnant women studied in a health axis. The means, the medians were calculated. Univariate and also bivariate analysis were performed. The Logistic regression were performed including all variables that p was less than 0.2. During the associations, the adjusted odd ratio (aOR) was evaluated with its 95% confidence interval; an association was considered statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study did not present any nuisance, the informed consent was signed by the participants and the University of Lubumbashi had authorized its realization.

General characteristics of the population In this series, concerning the retrospective study (Table 1), we collected 2400 patients from rural (1200) and urban (1200) areas. The majority of patients were more than 18 years old (96%, n=2104). The mean of the age was 25.9 ± 6.57 years, extremes 12 and 47 years. They were household (85%, n= 2040) and maried (95.6%, n=2288). However, it also indicates that there were fewer singles (4.7%, n=112) and fewer workers of private or public institution (2.83%, n=68). Concerning the prospective study, 128 patients were collected in the third trimester of the pregnancy from low income (52) and high income (76) population

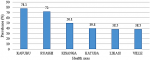

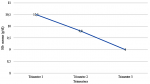

Prevalence and severity of Anemia in Lubumbashi The prevalence of anemia in Lubumbashi was 52.8%; it varies around 78% in rural areas and a little less than 40% in urban areas (Figure 1). In the entire third trimester study population, three out of five pregnant women were anemic. In the low income population, 84.6% (Four out of five) were anemic and in the high income population, 42.11% (Two out of five) of pregnant women were anemic. Depending on the severity of anemia, anemia in pregnant women was deeper in rural than in urban areas as shown by the increase in severe anemia from 0.8% in urban area to 1.5% in rural area and moderate anemia from 39.2% in urban area to 49.9% in rural area. In addition, mild anemia decreases in rural areas (from 60% in urban area to 48.6% in rural area) in favor of moderate anemia. Furthermore, severe anemia is very poorly represented in both settings. The hemoglobin means decreased as the pregnancy progressed. It was 10.5 g/dl, 9.8 and 9 respectively in the first, second and third trimester (Figure 2)

Risk factors for anemia in pregnancy The associated factors of anemia were multiple (Table 2). This was the case for the age under 18 years, living in a rural area, a large family, the prenatal consultation less than 3 and malaria. After logistic regression concerning all factors that have a p value less than 0.2, three associated factors were retained. It was a large family (aOR 1.30, 95% CI 1.09-1.54; p=0.003); living in a rural area (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.20-1.42; p=0.0001) and malaria (aOR 1.95, 95% CI 1.54-2.31; p=0.0001).

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy in Lubumbashi and to identify the associated factors. Anemia affects 38.5-84.6% in pregnant women. Its associated factors were a large family, living in a rural area and malaria. This study showed that the prevalence of anemia in Lubumbashi reached 52.8%. It reaches 78% and 38.5% a in rural and urban areas. Indeed, anemia is disproportionately concentrated in disadvantaged socio-economic groups [11-16]. The proportions of anemia in Lubumbashi has not changed for more than three decades despite the appearance of the modernization of the city. The prevalence of anemia increased as the pregnancy approached term [17-19]; Hb means gradually declined from 10.5 in the first trimester to 9 in the third trimester. The associated factors were multiple: they were a large family, living in a rural area and malaria. Many other studies give the same results [20-22].

We carried out a retrospective cross-sectional descriptive study on anemia in pregnancy and obtained the results summarized below. The prevalence of anemia remains high in Lubumbashi. It affects two to four pregnant women out of five. The associated factors for anemia in pregnancy were the age under 18, living in rural area and malaria. It is essential to strengthen control and prevention measures in Lubumbashi.

What is known about this topic

- Anemia during pregnancy is more common in developing countries than in developed countries;

- The disadvantaged populations are the most victims.

What this study adds

- The proportions of anemia in Lubumbashi has not changed for more than three decades despite the appearance of the modernization of the city;

- Prevalence of anemia in pregnancy in Lubumbashi, situation in 2020 was 52.8%;

- Associated factors of anemia in pregnancy in Lubumbashi in 2020 were a large family, living in a rural area and malaria.

The authors declare no competing interests.

All authors contributed to this work. They equally read and approuved the final version of the article.

We thank all directors to authorize us to realize this study in their respective hospitals.

Table 1: sociodemographic characteristics

Table 2: associated factors of anemia in pregnancy

Figure 1: prevalence of anemia in pregnancy in Lubumbashi

Figure 2: evolution of Hb means and anemia during pregnancy

- Li L, Yumei W, Weiwei Z, Chen Wang, Rina S, Hui F et al. Prevalence risk factors and associated adverse pregnancy outcomes of anaemia in Chinese pregnant women: a multicentre retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):111. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nyamu GW, Kihara JH, Oyugi EO, Omballa V, El-Busaidy H, Jeza VT. Prevalence and risk factors associated with asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infection and anemia among pregnant women at the first antenatal care visit: a hospital based cross-sectional study in Kwale County. Kenya. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0239578. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kalenga MK, Nyembo MK, Nshimba M, Foidart JM. Étude de l'anémie chez les femmes enceintes et les femmes allaitantes de Lubumbashi (République Démocratique du Congo): Impact du paludisme et des helminthiases intestinales. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2003;32(7):6647-653. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Elizabeth MM, Steven RM, Peter M, Indu M, Christopher LK, Robert L G et al. The association of parasitic infections in pregnancy and maternal and fetal anemia: a cohort study in coastal Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014 Feb 27;8(2):e2724. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ononge S, Campbell O, Mirembe F. Haemoglobin status and predictors of anaemia among pregnant women in Mpigi, Uganda. BMC Res Notes . 2014 Oct 10;7:712. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Patel A, Prakash AA, Das PK, Gupta S, Pusdekar YV, Hibberd PL. Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: cohort study in eastern rural Maharashtra, India. BMJ Open. 2018 Aug 8;8(8):e021623. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kalaivani K. Ramachandran P. Time trends in prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 2018 Mar;147(3):268-277. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Cochrane WG. Sampling techniques 3. New York: Wiley; 1977.

- WHO. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005; WHO Global Database on Anaemia . 1993-2005. Consulté le 22 Novembre 2020.

- Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM). Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP) et ICF International. 2014. Enquête Démographique et de Santé en République Démocratique du Congo 2013-2014. Rockville. Maryland. USA: MPSMRM. MSP et ICF International.

- Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet . 2011 Dec 17;378(9809):2123-35. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Marjorie AM, Yusuf BB, Magaret K, Abdulrahman L. Determinants of anaemia among pregnant women in rural Uganda. Rural Remote Health. Apr-Jun 2013;13(2):2259. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sharma S, Kaur SP, Lata G. Anemia in pregnancy is still a public health problem: a single Center Study with Review of Literature. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2020 Jan;36(1):129-134. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Dim CC, Onah HE. The prevalence of anemia among pregnant women at booking in Enugu. South Eastern Nigeria. MedGenMed . 2007 Jul 11;9(3):11. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wemakor A. Prevalence and determinants of anaemia in pregnant women receiving antenatal care at a tertiary referral hospital in Northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Dec 11;19(1):495. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kalenga MK , Mutach K , Nsungula K, Odimba FK , Kabyla I. Les anémies au cours de la grossesse. Étude clinique et biologique. A propos de 463 cas observés à Lubumbashi (Zaïre). Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1989 May;84(5):393-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sun D. McLeod A. Gandhi S. Malinowski AK. Shehata N. Anemia in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017 Dec;72(12):730-737. PubMed | Google Scholar

- He GL, Sun X, Tan J, He J, CX Liu CX, Fan L et al. Survey of prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women in urban areas of China. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2018 Nov 25;53(11):761-767. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Zhao SY, Jing WZ, Liu J, Liu M. Prevalence of anemia during pregnancy in China 2012-2016: a Meta-analysis. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018 Sep 6;52(9):951-95. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Shulman CE, Dorman EK. Importance and prevention of malaria in pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Jan-Feb 2003;97(1):30-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kalra S. Khandelwal D. Singla R. Aggarwal S. Dutta D. Malaria and diabetes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017 May;67(5):810-813. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nandlal V. Moodley D. Grobler A. Bagratee J. Maharaj NR. Richardson P. Anaemia in pregnancy is associated with advanced HIV disease. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 15;9(9):e106103. PubMed | Google Scholar