Exserohilum rostratum keratitis: report of a case from South Africa

Jonathan Timothy Oettlé

Corresponding author: Ophthalmology Department, Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital, Ophthalmology Department Provincial Hospital, Port Elizabeth, South Africa.

Received: 06 Jan 2022 - Accepted: 01 Feb 2022 - Published: 02 Feb 2022

Domain: Infectious disease,Ophthalmology

Keywords: Exserohilum, rostratum, keratitis, South Africa, ophthalmology, case report

©Jonathan Timothy Oettlé et al. PAMJ Clinical Medicine (ISSN: 2707-2797). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Jonathan Timothy Oettlé et al. Exserohilum rostratum keratitis: report of a case from South Africa. PAMJ Clinical Medicine. 2022;8:26. [doi: 10.11604/pamj-cm.2022.8.26.33132]

Available online at: https://www.clinical-medicine.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/8/26/full

Exserohilum rostratum keratitis: a case report from South Africa

&Corresponding author

We report a case of infectious keratitis caused by the fungal pathogen Exserohilum rostratum in an immune-competent patient in South Africa. A 67-year-old man with hypertension presented with a painful red left eye two weeks after trauma with an organic foreign body. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy revealed a corneal ulcer with underlying stromal infiltrates, feathery margins and a hypopyon. Exserohilum rostratum was identified using fungal PCR testing on culture grown from a corneal scrape, and the patient responded to topical 5% natamycin eye drops. Corneal scarring limited final visual outcomes to Counting Fingers at 50cm. In conclusion, E. rostratum keratitis was previously rare, but is now considered an emerging corneal pathogen which can occur in temperate climates.

Fungal pathogens are a common cause of infectious keratitis worldwide [1], with Aspergillus, Fusarium and Candida species being the most prevalent [2]. The pigmented filamentous, or dematiaceous, fungi are increasingly being identified as human pathogens [3] and are known to cause systemic, cutaneous and corneal infection [4]. The term phaeohyphomycosis was coined in 1974 to refer specifically to infection by melanin-containing fungi [5]. The dematiaceous fungi include the genus Exserohilum, of which three species cause mycosis in humans, namely E. rostratum, E. longirostratum and E. mcginnissii [3,6]. E. rostratum is the most common [4], and is emerging as a keratomycosis of importance [7]; it occurs more commonly in hot tropical and subtropical climates, such as India [7,8]. This report describes a case of Exserohilum rostratum keratitis from South Africa.

Patient information: a 67-year-old male was referred to our tertiary eye centre by a local primary health care facility with a two-week history of a painful red left eye. The initiating event was trauma with an organic foreign body while chopping wood. He had systemic hypertension and a 40 pack-year smoking history, but no other relevant medical or ocular history.

Clinical findings: on presentation, the patient had 6/5 vision in the unaffected right eye and hand motions in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 18 and 21 mmHg, respectively. The right eye was ophthalmologically normal. In the left eye, the conjunctiva was injected and there was a central corneal ulcer of 4.0mm x 3.8mm, with thick plaque overlying the ulcer base. The cornea was thinned under the ulcer, and corneal sensation was normal. There was a stromal infiltrate with feathery margins underlying the ulcer to a depth of approximately 75%, and a blood stained hypopyon in a deep anterior chamber. There was no view to the fundus, but pupil responses and light projection were normal.

Timeline of events: on the day of presentation, the patient was admitted to our ophthalmology ward, corneal scrapings were sent for gram stain, bacterial and fungal cultures, and topical antibiotics were initiated. Staphylococcus hominis was identified on day four, sensitive to vancomycin and gentamicin. Fungal cultures showed a mould of unknown species on day eight of admission; antifungals were started. The mould was initially identified as Exserohilum rostratum by mass spectrometry; this was confirmed on day 14 using fungal PCR on samples from the fungal culture. On starting appropriate antifungal therapy, the patient began to improve clinically, and was discharged on day 21. The patient was followed up at day 5, 8, 12, 16, 19, 26, 33, 46, and 74 after discharge, at which point antifungal treatment was stopped, and the patient was referred to optometry for refractive optimisation Table 1.

Diagnostic assessment: corneal scrapings taken 21/04/2021: Staphylococcus hominis, sensitive to vancomycin and gentamycin; Exserohilum rostratum - no sensitivity reported.

Therapeutic intervention: topical moxifloxacin 5mg/ml 2-hourly was initiated on admission; this was changed to topical cefazolin 50mg/ml and gentamicin 15mg/ml hourly on day three as there was no clinical response. The cefazolin was changed to topical vancomycin 50mg/ml 3-hourly on day four in response to antibiotic sensitivity results. The superficial plaque overlying the ulcer was debrided on day seven of hospital stay. Topical 5% natamycin 2-hourly was started on day eight in response to growth on the fungal culture plate, and continued until 13 weeks after diagnosis. The corneal ulcer reduced in size and the hypopyon resolved slowly after starting natamycin. On day 19 topical antibiotics were stopped, and autologous serum eye drops 4-hourly with oral vitamin C 500mg 8-hourly were initiated.

Follow up and outcome: the patient spent 21 days in hospital, and was followed up closely for a further eleven weeks, during which time he continued to improve slowly. Natamycin, autologous serum and vitamin C were continued for eleven weeks after discharge, after which they were stepped down to simple lubricants only. The total treatment time with antifungals was 13 weeks. The affected cornea healed with scarring, and the final visual outcome was counting fingers at 50cm (LogMAR +2.00).

Patient perspective: the patient reported subjective improvement in pain and visual symptoms during his treatment, and was satisfied with the care received. He complied with treatment during and after his hospital stay, and although disappointed at the poor visual outcome he continues to follow up routinely at our eye clinic.

Informed consent: the patient was counseled about participation in the study, and an informed consent document was signed.

Ethics: the report was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Studies at Walter Sisulu University, and was conducted in accord with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

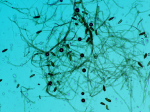

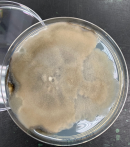

Exserohilum species are a family of fungi commonly found in wood, organic material, grass and soil [7-9]. They prefer warm, moist environments and are more common in tropical and subtropical climates [7]. They are classified as dematiaceous fungi, which produce pigmented moulds due to melanin production [10]. Microscopically, all three species of Exserohilum have a characteristic hilum, and can be distinguished by the morphological appearance of their conida [8,11]. Conida can be seen in Figure 1, Figure 2 demonstrates mould pigmentation. Exserohilum has been known to cause a broad range of disease in humans, including systemic and topical phaeohyphomycosis affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue, nose and paranasal sinuses, as well as endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis and keratitis [4,12]. Impaired immunity is the main risk factor for systemic and skin infection [4]; corneal trauma and diabetes are the main risk factors for keratomycosis [7]. Corneal infection was previously relatively rare, with only eight cases described before the outbreak from contaminated methylprednisolone in the USA in 2012 [13], but recently has become recognised as an important emerging corneal pathogen [7]. Most of the reported cases are from India, Israel, and the southern United States [4,7]; this report describes the first case from Africa. Decreased corneal sensation has been described [13], but sensation was normal in our patient.

Exserohilum species have been described in multi-organismal keratitis [14], but a corneal specialist whom we consulted was of the opinion that in this case the Staphylococcus hominis was likely a contaminant of no clinical significance, as there was no clinical improvement to antibiotics with proven sensitivity. There was a good clinical response to topical natamycin, in keeping with the majority of reports [7,13,15]. A recent review of 47 patients from India [7] described a mean final visual acuity of LogMAR 0,77 (Snellen 6/36), considerably better than in our patient, who achieved counting fingers at 50cm (LogMAR +2,0) after completion of treatment. Possible reasons for the poor visual outcome include delayed presentation, late identification of the fungal pathogen and initiation of antifungal treatment, and central corneal scarring. Treatment regimens are often prolonged [7,13], and our patient required more than three months of topical antifungals. Good documentation, patient compliance, and antimicrobial treatment according to best available evidence were strengths in this case. Limitations included resource constraints, few special investigations, and delays in accessing healthcare.

Exserohilum rostratum is an emerging corneal pathogen of increasing global importance and is not confined to tropical and subtropical zones, but can also occur in temperate climates.

The authors declare no competing interests.

All the authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr S. M. Dave for supervision of the project, Dr N. York for valuable input and guidance, and Dr S. Abrahams, Mrs V. Pearce and Mrs M. Ndalamo from the National Health Laboratory Services for the provision of microscopy images.

Table 1: timeline of events

Figure 1: lactophenol cotton blue wet preparation demonstrating conida

Figure 2: macroscopic appearance of the mould demonstrating pigmentation

- Srinivasan, M. Fungal keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004 Aug;15(4):321-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Rao GN. The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: a 10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea. 2002 Aug;21(6):555-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Adler A, Yaniv I, Samra Z, Yacobovich J, Fisher S, Avrahami G et al. Exserohilum: an emerging human pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006 Apr;25(4):247-53. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Katragkou A, Pana ZD, Perlin DS, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Exserohilum infections: review of 48 cases before the 2012 United States outbreak. Med Mycol. 2014 May;52(4):376-86. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, Wang CJK. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66(3):490-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, Pullen R, Rinaldi MG. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Feb 15;34(4):467-76. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Rathi H, Venugopal A, Rameshkumar G, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R. Fungal keratitis caused by Exserohilum, An emerging pathogen. Cornea. 2016 May;35(5):644-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Oct;23(4):884-928. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Forster RK, Rebell G, Wilson LA. Dematiaceous fungal keratitis. Clinical isolates and management. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975 Jul;59(7):372-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A. Impact of melanin on microbial virulence and clinical resistance to antimicrobial compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006 Nov;50(11):3519-28. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Peerapur BV, Rao SD, Patil S, Mantur BG. Keratomycosis due to Exserohilum rostratum - a case report. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22(2):126-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- McGinnis MR, Rinaldi MG, Winn RE. Emerging agents of phaeohyphomycosis: pathogenic species of Bipolaris and Exserohilum. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Aug;24(2):250-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Chaidaroon W, Phaocharoen N, Srisomboon T, Vanittanakom N. Exserohilum rostratum keratitis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2019 Apr 17;10(1):127-133. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Qiu WY, Yao YF. Mycotic keratitis caused by concurrent infections of Exserohilum mcginnisii and Candida parapsilosis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013 Aug 1;13(1):37. PubMed | Google Scholar

- da Cunha KC, Sutton DA, Gené J, Capilla J, Cano J, Guarro J. Molecular identification and in vitro response to antifungal drugs of clinical isolates of Exserohilum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Sep;56(9):4951-4. PubMed | Google Scholar